PC

T&P

| |

PERSONAL CONSTRUCT

THEORY & PRACTICE

|

Vol.5 2008 |

| PDF version |

| Authors |

| Reference |

| Journal Main |

| Contents Vol 5 |

| Impressum |

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DISCLOSING CHILDHOOD SEXUAL ASSAULT IN CLOSE RELATIONSHIPS:

THE MEANINGS AND EMOTIONS WOMEN ASSOCIATE WITH THEIR EXPERIENCES AND THEIR LIVES NOW |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hilary A. Maitland and Linda L. Viney | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| School

of Psychology, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, Australia |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

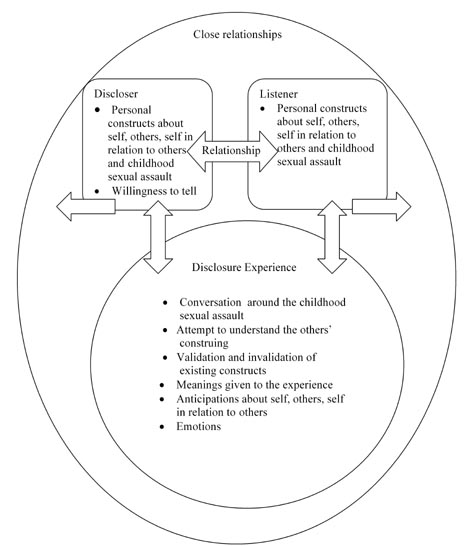

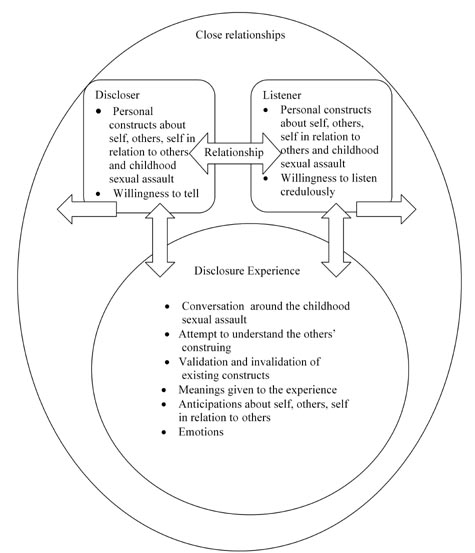

The psychology of personal constructs (see Kelly, 1955/1991) provides a respectful and hopeful framework in which to explore the experiences of women assaulted as children, and who had chosen to tell of their experiences to people with whom they were in close relationships. This approach is respectful since, while recognizing the shared nature of experiences and meanings people bring to experiences, it also recognizes the importance of individual women’s experiences and their views of themselves and their worlds. It is also hopeful since its basic assumption, constructive alternativism (see Kelly, 1955/1991), is a source of optimism. It recognises that there is no limit to the way in which people can make sense of experiences. There is always another way of looking at events that may open up options for healthier living (Kelly, 1955/1991). The research was conducted within a qualitative framework, which fits well with a personal construct framework. In this research we accepted women’s accounts of their disclosure experiences, to be their recollections at the time they shared them with us, of what they believed happened when they disclosed. Personal construct psychology proposes that it is how people make sense of experiences, rather than the experiences alone, that influences how they view self, others and self in relation to others. The psychology of personal constructs also suggests that these meanings will change over time as people continue to try to make sense of their lives. We developed a model of the disclosure processes for women within which to explore their experiences. Our model stressed the relational nature of disclosure and the importance of the meanings both the discloser and the listener bring to these situations. Our model proposes that both women disclosing and their listeners bring their own ways of making sense of their world with them to disclosure experiences while at the same time endeavoring to understand the meanings the other gives to experiences. Disclosure provides opportunity for invalidation and validation of meanings about self, others, self in relation to others and childhood sexual assault for both women disclosing and their listeners. This invalidation and validation will influence women’s personal meanings about self, others, self in relation to others (Leitner, 1985; Leitner, 1988; Faidley & Leitner,1993; Leitner & Faidley, 1995) and childhood sexual assault. These personal meanings will lead to further anticipations about self and self in relation to others resulting in a variety of emotions .The particular emotions of women disclosing will be associated with different activity within their meaning making systems and the meanings and anticipations to which these give rise (see Kelly 1955/1991; McCoy, 1977; Miall, 1989). Emotions will be unique for each disclosure experience and for each woman. Each disclosure experience will influence the likelihood of future disclosure and will impact on women’s current meanings about childhood sexual assault, self, others and self in relation to others (relationships). Figure 1 illustrates our model. It demonstrates the circular nature of the disclosure experience for the discloser and the listener.  Figure 1: A personal construct model of the processes involved in women's disclosure of childhood sexual assault The questions that followed from our aim to explore women’s experiences included:

METHOD Sampling Participants were twenty-eight (28) women for whom disclosure processes were still relevant, as evidenced by their continuing access to counselling support services. The selection of participants for this research was ‘purposive’ in that they were seen as being able to provide rich data about the disclosure of childhood sexual assault in close relationships, something that we believed would be both useful and relevant to psychotherapists working with these women and others like them in the health service setting (see Polkinghorne, 2005; Morrow, 2005; Gerhard, Ratliff & Lyle, 2001). Forty eight percent (48%) of women were aged between 20 and 35 years while fifty two percent (52%) were aged between 41 and 60 years. The women had been sexually assaulted prior to the age of 14 years by a person with whom they were in a close relationship (see Figure 2).  Figure 2: Percentage of women abused as children by relationship to abuser Thirty five percent (35%) of the women had been assaulted by one person while sixty five percent (65%) had been assaulted as a child by more than one person. The majority of perpetrators were male. The greatest percent of women (79%) were first assaulted between the ages of 3 and 8 years, nine percent (9%) were first assaulted under 2 years and thirteen percent (13%) between the ages of 9 and 14 years. Nine percent (9%) of participants had been assaulted more than once while ninety one percent (91%) were assaulted over an extended period of time. Sixty one percent (61%) had also been sexually assaulted as adults. The majority of women (31%) disclosed to their mothers. Women also disclosed to counsellors (19%), sisters (8%), fathers (4%) and friends (8%). Thirty one percent (31%) had disclosed to others but did not say to whom. Procedure Women who were attending three different services for survivors of childhood sexual assault were invited to participate in the research. Twenty three women participated individually by providing information about themselves and their experiences in written form. They were provided packages containing a sexual assault/disclosure questionnaire which gathered demographic information and information about their assault experiences. Paper on which to record an account about the their life as they viewed it at the time of the research and paper on which to record an account about an important past disclosure experience was supplied (based on the method developed by Gottschalk & Gleser,1969, Viney & Caputi, 2005) and the Social Support Questionnaire-SSQ (Sarason, Levine, Basham & Sarason, 1983). The Social Support Questionnaire was included as one measure of participant’s meanings about their relationships. The Social Support Questionnaire consists of twenty-seven (27) questions designed to provide information on the extent of people’s social support and the level of satisfaction they perceive in relation to the support they receive from others. These questions ask the person completing the questionnaire to list those people:

Sarason Levine, Basham and Sarason (1983) and Heitzmann and Kaplan (1988) present research findings establishing the reliability and validity of the SSQ (test retest reliability of .90 for SSQN (measuring the number of people in an individual’s support network) and .83 for SSQS (measuring the individuals satisfaction with their social support); internal consistency of .97 for SSQN and .94 for SSQS; and appropriate correlations with other measures). Eight women also participated in a support group discussion morning. This provided opportunity to explore women’s initial disclosure experiences in more depth using a number of structured questions developed in collaboration with the Group facilitator. DATA ANALYSIS The meanings, emotions and relationships in individual women’s accounts of their experiences (narratives) were explored using thematic analysis. Using the methods outlined by Miles and Huberman (1994) two people independently read all transcripts to identify meanings using meaning codes. These codes were initially developed based on a review of the literature in relation to childhood sexual assault and disclosure and clinical experience with survivors of childhood sexual assault. Both raters followed a set of instructions detailing the process of coding. The inter- rater agreement for these ratings was 0.77 (calculated using the formula: agreements divided by (agreements plus disagreements) as recommended by Boyatzis (1998) which was considered acceptable (see Miles & Huberman ,1994; and Boyatzis 1998). These meanings were then explored further by grouping them to enable the clustering of meanings and across case comparisons presented as data displays (see Miles & Huberman, 1994; Boyatzis, 1998). The following questions guided this process:

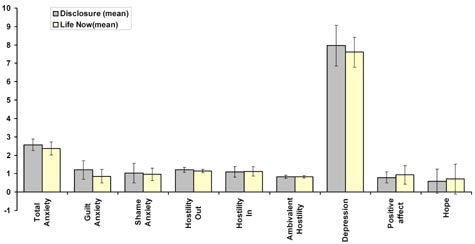

The LIWC 2001 was developed “to provide an efficient and effective method for studying the various emotional, cognitive, structural and process components present in individuals’ verbal and written speech samples” (Pennebaker, Francis & Booth, 2001, p.12). The selection of words used to define the LIWC2001 categories occurred over a number of years and involved the compilation of broad word lists that were further refined in 1992-1994 and again in 1997. Support for the reliability and validity for the LIWC 2001 was established by comparing LIWC scales and judges ratings for the same categories and are presented in the manual. The LIWC 2001 is inherently reliable since it will score the same transcript the same way every time. Content analysis of narratives using well-established content analysis scales to assess emotions and relationships (Gottschalk & Gleser, 1969; Westbrook, 1976; Viney & Westbrook, 1979; Viney & Caputi, 2005) was undertaken using the PCAD 2000 (Psychiatric Content Analysis and Diagnosis 2000) for the content analysis of the Anxiety (Threat) Scale, Hostility Directed Outward Scale, Hostility Directed Inward Scale, Ambivalent Hostility Scale, Depression Scale, Hope Scale, and Human Relations Scale and a computer assisted scoring program, Analyse (see Viney, Caputi & Webster, 2000) to score the Positive Affect and Sociality Scales. The Anxiety Scale measures “death, mutilation, separation, guilt, shame, and diffuse or nonspecific anxiety” (Gottschalk & Gleser, 1969, p. 22). The Hostility Scales were designed to measure “the anger portion of the hostility concept” (Gottschalk & Gleser, 1969, p. 31) and focus on the direction of the hostility, that is, hostility directed away from the self (Hostility Outward Scale) including “adversely critical, angry, assaultive, asocial impulses and drives toward objects outside oneself ” (Gottschalk & Gleser, 1969, p. 32), hostility directed toward the self (Hostility Inward Scale) including “self hate and self criticism and, to some extent, feelings of anxious depression and masochism”( Gottschalk & Gleser, 1969, p. 32) and ambivalently directed hostility (Ambivalent Hostility Scale) “suggesting destructive and critical thoughts or actions of others to the self” (Gottschalk & Gleser, 1969, p. 32) but also including some aspects of inward and outward directed hostility. The Human Relations Scale is designed to measure “an individual’s degree of interest in and his capacity for constructive, mutually productive, or satisfying human relationships” (Gottschalk & Gleser, 1969, p. 220) which is relevant to the study of close relationships. The Hope Scale is designed to measure “the intensity of the optimism that a favourable outcome was likely to occur, not only in one’s personal earthly activities, but also in cosmic phenomena and even in spiritual or imaginary events” (Gottschalk & Gleser, 1969, p. 247). . Gottschalk & Gleser (1969) report a number of studies examining the validity of the Anxiety Scale (comparing the Gottschalk-Gleser anxiety scale to other measures including clinical psychiatric interviews, self report measures, adjective checklists, clinical ratings of Thematic Apperception stories, psychotherapeutic interviews, psychobiological and psychobiochemical studies). The Hostility Scale scores have been examined in studies designed to compare the three types of hostility with other measures of hostility including adjective checklists, ratings on psychiatric rating scales, psychiatric evaluation of hostility, psychotherapeutic interviews, Thematic Apperception stories, psycho-physiological studies, psychopharmacological studies, and psycho-biochemical studies (Gottschalk & Gleser, 1969). The scales included in the final development of the computerised version, PCAD 2000 (GB Software, Gottschalk & Bechtel, 2002) are an extension of the original scales developed by Gottschalk and Gleser (1969). The Depression Scale designed to measure the construct of depression (which includes hopelessness, self-accusation, psychomotor retardation, somatic concerns and death and mutilation depression) is relevant to the study of emotions around the disclosure of childhood sexual assault. The development of computerised scoring for content analysis scales has been undertaken over a considerable period of time beginning in 1975 with the latest version of the PCAD 2000 released in 2003. The PCAD 2000 is able to “do a reliable job of scoring the Gottschalk-Gleser Anxiety and Hostility scales, but it also derives scores on the Social Alienation Disorganisation, Cognitive Impairment, Depression, and Hope Scales.” (GB Software, Gottschalk & Bechtel, 2002, p. 41). Inter-scorer reliability between human raters and an earlier version of the PCAD 2000 for the Anxiety and Hostility Scales was 0.80 and above. The Positive Affect Scale (Westbrook, 1976) is designed to assess positive feeling states “that are usually considered pleasurable, agreeable or desirable as opposed to negative affects that are considered unpleasant” (Westbrook, 1976, p. 716). Normative data for five groups was provided in the development of the scale. The Positive Affect scale will be used as one measure of positive emotions in this research. The Sociality Scales (Viney & Westbrook, 1979) are designed to “assess the extent to which a person is currently experiencing satisfying interpersonal relationships” (Viney & Westbrook, 1979, p. 129). The Sociality Scale has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid tool for tapping people’s positive interpersonal relationships (Viney & Westbrook, 1979). This Scale along with the Human Relations Scale and the SSQ will be used to measure women’s interpersonal relationships. Viney, Caputi and Webster (2000) and Viney and Caputi (2005) reviewing the Positive Affect Scale present an overview of studies demonstrating satisfactory inter rater reliability and validity. Viney and Caputi (2005, p. 121) indicate validity is demonstrated by the fact that the Positive Affect Scale scores “are independent of gender, age, and occupational status but are related to scores on other positively toned measures…and negatively related to scores on negatively toned measures.” Viney, Caputi and Webster (2000) reviewing the Sociality Scales present an overview of studies demonstrating satisfactory inter rater reliability, internal consistency, stability, and validity (e.g., independent of gender, age and occupational status, scores are related negatively to scores of negatively toned states, and they are able to discriminate between groups of people as anticipated). Viney, Caputi and Webster (2000) outline a computerised scoring system “Analyse” that enables computer assisted scoring for a number of scales including the Positive Affect Scale and the Sociality Scales. As with the PCAD 2000 this program helps overcome some of the difficulties encountered when attempting to score the content analysis scales manually and ensure good inter rater reliability. RESULTS Meanings about disclosure and life now Meanings about self Meanings about being accepted/not being accepted, being different from/similar to others, feeing loved/not loved, experiencing pain/no pain, seeing themselves as valuable/not valuable and whole/not whole were present in women’s narratives of disclosure and life now. A higher percentage of women included meanings about being accepted/not accepted than other meanings about self in disclosure narratives, while being accepted/not accepted and feeling loved/not loved were the most prominent meanings identified in women’s life now narratives. Meanings about self in relation to others Meanings about control/lack of control in relationships, family/lack of family, friends/lack of friends, intimacy/lack of intimacy in relationships, being isolated/not isolated, love/lack of love in relationships, open/not open in relationships, feeling safe/not safe in relationships, having support/lack of support in relationships, and trust/lack of trust in relationships were identified in women’s narratives of disclosure and life now. Meanings about family/lack of family and support/lack of support in relationships were the most prominent in women’s disclosure narratives. Meanings about family, friends and intimacy were most prominent in women’s life now narratives. Between forty percent (40%) and fifty percent (50%) of women identified meanings around trust as important for them in both their disclosure and life now narratives. Exploring support further indicated that the majority of women relied most on the support from professionals. Approximately half of the women were attending counselling and specialist support groups, however, support from family (26%) and friends (17%) was also important to them. Exploring meanings around self in relation to others in the Support Group, indicated that women received a mixture of reactions from their listeners, with some receiving support and feeling understood while others indicating their listeners did not offer support or understand how they were feeling at the time. From the Support Group it was evident that the relationships with the person to whom women initially disclosed changed following disclosure. The changes included increased intimacy, when their listener was able to understand them better, or reduced intimacy, when their listener’s were not able to accept the women’s story with the latter, negative reaction, being most common. The Support Group also illustrated the importance of disclosure on women’s willingness to trust others with whom they were in close relationships. A mixture of reactions was apparent. Some women indicated they were reluctant to trust, others indicated they had changed the way they trusted and who they trusted since disclosure, while others indicated they were comfortable with trusting others. Meanings about assault Meanings about being betrayed/not betrayed, blamed/not blamed, denying the assault/not denying the assault, the assault being secret/not secret, and listener’s wanting to know/not want to know about the assault were present in women’s narratives of disclosure. Meanings about betrayal were absent from women’s life now narratives. Meanings about assault were less prominent in women’s narratives for life now than they were for disclosure. This indicates that when talking about their life in the present, women’s childhood sexual assault was not a central feature for them, although its impact may be seen in their narratives. Meanings about disclosure Meanings about being believed/not believed, being heard/not being heard, telling/not telling others, and feeling they were understood/not understood were present in women’s narratives of disclosure and life now. All these meanings, apart from feeling they were or were not understood, were much less prominent in women’s life now narratives. This indicates that when women disclose personal details about themselves, either at disclosure or as part of their everyday experiences, the reactions of their listeners’ is important to them, especially, being believed, heard and understood. Unfortunately many women in this research were not met with belief and support. Exploring meanings about being believed further revealed that over 70% of women indicated they were believed at the time of disclosure, of those women who were believed one third were either blamed for the sexual assault or their listener took no action to help them following disclosure. Also, of those women who indicated they were believed by their listeners, almost half were encouraged to keep it secret. One third of the women who were believed by their listeners indicated their listeners did not want to know details about the assault or to talk about it following the disclosure. The Support Group further illustrated the impact of listener’s reactions on women’s willingness to share their stories of assault with others. A mixture of responses were reported by women, with some women (especially those who had received unhelpful responses) indicating reluctance to share with others, some were very careful about who they were willing to tell, while others indicated that withholding disclosure from people with whom they were in very close relationships was counter productive, viewing telling as essential for intimate relationships. Meanings about recovery Meanings about the importance of counselling and about recovery/lack of recovery were present in women’s narratives about disclosure and life now. Both were more prominent in women’s life now narratives than they were in their narratives about disclosure. Almost ninety percent (90%) of women made reference to recovery in their life now narratives. Meanings about the quality women associated with their lives Meanings about change were more prominent in women’s disclosure narratives than life now narratives. Meanings about having a future/no future, life being ok/not ok, turmoil/stability, and having hope/no hope were more prominent in women’s life now narratives than in their disclosure narratives. Satisfaction with their lives in the present was important for women, with many of them indicating that their lives lacked the things they really wanted to be truly satisfied, especially intimacy in their relationships. Invalidation, validation and re-construction Invalidation, validation and re-construction were explored by looking at women’s anticipations about how their listener’s would react, how they reacted and how they felt about those reactions and their narratives. This was done by examining women’s narratives and by their answers to question 13 of the sexual assault/disclosure questionnaire were examined. Question 13 asked, “Before you told this person how did you expect they would respond?" Thirteen percent (13%) of women had no prior anticipations, twenty two percent (22%) had anticipations that their listener’s reactions would be non-supportive, thirty five percent (35%) anticipated their listener’s reactions would be supportive, twenty six percent (26%) anticipated both non-supportive and supportive reactions from their listeners and four percent (4%) of women’s anticipations were unknown. Figure 3 indicates the extent to which these anticipations were validated.  Figure 3: Women's anticipations about listener's reactions prior to disclosure that were invalidated, validated or neither invalidated or validated These results indicate that listener’s reactions invalidated, validated or provided neither invalidation or validation for women’s anticipations regardless of whether women expected support or no support. Women’s narratives also provided evidence for invalidation and validation (for example, when listers did not believe or believed what women told them respectively).  Figure 4: Changes in how women felt about listener's reactions to their disclosure Looking at the emotions women associated with their listener’s reactions to disclosure in Figure 4 indicates that there had been some changes to how they felt about their listeners’ reactions in the present from how they had felt at the time of disclosure. These changes provide evidence that the meanings women had given to these had changed over time (evidence of re-construction). Women’s narratives also included statements to suggest that how they viewed their disclosure experience had changed over time (e.g., “I am starting to look at incest from another side”, “I feel now that I trusted too quickly”) Negative and positive emotions were evident in women’s narratives of disclosure and life now, namely, anger, hostility, anxiety, fear, mixed emotions, guilt, shame, sadness/depression, love, pleasant emotions in general, and relief. Hostility and relief were identified only in women’s narratives of disclosure, while love was identified only in women’s narratives of life now. A higher percentage of women reported anger, anxiety, guilt, sadness/depression and positive emotions in their life now narratives than disclosure narratives. Content analysis scales showed evidence of threat, guilt, shame, hostility, depression, positive affect and hope with depression being the most prominent affect in both disclosure and life now narratives (see Figure 5).  Figure 5: Means and standard deviations for content analysis scales measuring the effect in women's narratives There were particular meanings that could be identified in women’s narratives associated with the emotions they experienced. In narratives about disclosure, fear was associated with the childhood sexual assault, while anger was associated with not being believed. Shame was associated with talking about the child sexual assault and not being believed. Sadness was associated with recalling the child sexual assault, seeing its impact on loved ones, their children’s abuse, and turmoil in their lives. Relief was associated with being able to tell their stories and being heard. Pleasant emotions were associated with the burden being lifted by telling and being told the abuse would stop. In narratives about life now, threat was associated with actual threats to women’s physical safety. Anxiety was associated with the unknown potential impact of women’s abuse on others, and fear with recalling the childhood sexual assault and everyday things. Anger was associated with being rejected by others, lack of supports and the child sexual assault. Shame was associated with how they thought about others. Sadness was associated with not being believed when they shared the childhood sexual assault, problems in relationships (especially lack of intimacy and support), confusion and struggling to survive daily. Pleasant emotions were associated with loving and supportive relationships. It was anticipated there would be an association between the emotions women experienced and their social networks, in particular their experience of satisfying close relationships. Pearson product moment correlations between negative affects and the four measures of relationships (SSQN, SSQS, Sociality Scale and Human Relations Scale) failed to reach significance. Pearson product moment correlation coefficients for positive affects and each of the measures of relationships are presented in Table 1. Table 1. Correlation coefficients for positive emotions and relationship measures

DISCUSSION These findings have important implications for women when looked at in conjunction with previous findings about disclosure showing that the need to continue talking about traumatic events will be there for as long as the memory of the event produces emotions (Rime, Finkenauer, Luminet, Zech & Philippot, 1998) and that sharing intense emotions is one way in which people can obtain the help and support they need from others (Pennebaker, Zech & Rime, 2001). Women in this study indicated that disclosure did not always provide them with the help and support they needed and that often the person to whom they disclosed did not want to continue talking about it following disclosure. Although previous findings highlight that the choice of person to whom women disclose is important (Pennebaker, 1990), the experience of women in this research indicates that women did not always select listeners who they anticipated to be supportive. Many women chose to disclose even though they anticipated negative reactions from their listeners, while others who selected listeners they anticipated to react supportively, were disappointed in their listener’s reactions. Women in this research were clear that the disclosure of childhood sexual assault changed the nature of their relationship with their listeners. Many of them viewed many of the difficulties they experienced in their daily lives as attributable to their past assault and the reactions they received at disclosure. The findings in relation to life quality are similar to earlier research that suggests women sexually assaulted as children may experience a lower level of life satisfaction (Fassler, Amodeo, Griffin, Clay, & Ellis, 2005). When looking at emotions, earlier studies (Lusk & Waterman, 1986; Lamb, 1986; Langtree, Briere & Zaide, 1991;Ystgaard, Hestetun, Loeb & Mehlum, 2004; and Fassler, Amodeo, Griffin, Clay, & Ellis, 2005) found similar negative emotions in women who had been sexually assaulted as children to those identified in this research. Our model emphasizes the importance of women’s close relationships, their meanings around self, self in relation to others and the childhood sexual assault. The meanings identified in women’s narratives of disclosure, their responses to questions about the anticipations they had about their listener’s reactions prior to disclosing, and responses of women to the questions discussed in the Support Group, provide support for our model. Women disclosing came to the disclosure experience with existing meanings or ways of making sense of self and others (e.g., meanings about being able to trust their listener, of receiving support or that they may not be believed). There was evidence that listeners also brought their own meanings to the disclosure experience, especially about the discloser and their responsibility for the sexual assault (e.g., comments, such as, “are you sure you did not come onto him” suggesting that the woman may have encouraged the assault, or seeing it as “exploration”). Women disclosing were willing to tell (e.g., wanted help following the assault, wanted to know what their listener knew about what was happening in the home). Disclosure involved a conversation around the childhood sexual assault involving attempts to understand each others’ meanings (e.g., “are you telling me your father was sexually assaulting you?”; “Do you believe him?”). Women received invalidation and validation of their existing meanings about self, others, self in relation to others, the childhood sexual assault (e.g., references to their listener not believing what they said or denying the abuse occurred, which invalidates the woman’s story and at the same time invalidates her as a construer of her life story). Listener’s reactions usually took the form of comments, although sometimes, it was what they did after the disclosure that provided invalidation and validation. Women gave meanings to their disclosure experiences, women made anticipations about future events based on these meanings (e.g., in relation to trusting others, being able to tell others to whom they were close, about the ongoing nature of their relationships with their listener) which affected how they behaved, their relationships after disclosure and consequently their emotions. There was also support for our model’s prediction that disclosure would have an impact on the relationship between discloser and listener and other close relationships. Women described changes to their relationships with their listeners following disclosure and women describe being cautious about other existing and subsequent close relationships following disclosure, especially in relation to intimacy, trust and openness, which indicates that disclosure impacts on women’s close relationships in general. The findings of this study indicate that four issues were very important for women at the time of disclosure, namely, that those with whom they have close relationships:

As credulous listeners, there is a requirement that they suspend their own meanings in order to accommodate the meanings provided by the discloser, even if they are discrepant from their own. Figure 6 presents a revised version of our model which acknowledges this important aspect of listener characteristics.  Figure 6: Revised personal construct model of the processes involved in women's disclosure of childhood sexual assault Being credulous listeners poses challenges for everyone. People develop their own individual meanings to make sense of their experiences. How do we avoid imposing our own meanings on other people’s experiences rather than understanding theirs? Kelly’s Sociality Corollary acknowledges the importance of being able to construe “the construction processes of another” (Kelly, 1955/1991, p.66) in social relationships. This does not mean that to have a relationship with someone people need to share common constructs, although on occasions they may (Kelly’s Commonality Corollary), but rather they need to be able to make the effort to see things through other people’s eyes (how they construe things). Being able to do this enables us to interact respectfully with others. Interacting in this way will help listeners avoid the difficulties that arise when they impose their own meanings on other’s experiences. The importance of the listener believing, showing this by supportive actions, willingness to listen and attempting to understand the discloser’s experience from their points of view remained important when women were describing their lives now. In addition to these issues, for life now, women also focused on the importance of intimacy in their close relationships, talking about the distress they felt over lack of intimacy, the struggle they had developing intimate relationships, or the positive impact of intimacy in close relationships. In fact, positive emotions and hope were associated with satisfying close relationships for life now. The four issues that women identified as important when disclosing to someone with whom they had a close relationship, are relevant for clinical practice. Counselling or psychotherapy is designed to provide a safe environment in which a close relationship will develop between the therapist/counsellor and his or her client. It is, therefore, very important that those working in clinical roles with women who have experienced childhood sexual assault, come to the therapeutic relationship in a manner that will both respect these women’s experiences and enable them to re-construe these so they can begin to live in the present in a way that will promote greater wholeness and health. Kelly (1955/1991, p. 121) drew attention to the importance of the therapist “taking what he sees and hears at face value [of taking] the credulous attitude”. The four issues that were important for women at the time of disclosure that impact on clinical practice, are also relevant to the wider community. It highlights the need for communities to recognize the importance for educating the general community about childhood abuse, especially sexual assault and for intensive support and education, for the families, especially non abusive parents and carers, of women sexually assaulted as children. The process of re-construction necessary for healing cannot occur in isolation. Other family members may also need to re-evaluate their meanings around the sexual assault and the woman who was assaulted. Future research designed to test the model and the usefulness of the qualitative methods employed in this research, with a greater variety of participants including non –clinical samples, and including understanding disclosure from the listener’s perspective would be appropriate. In summary, this research demonstrated the usefulness of our personal construct model of disclosure and a qualitative approach, focusing on detailed exploration of individual experiences, when trying to better understand women’s experiences of the disclosure of childhood sexual assault. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| REFERENCES | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Erbes, C. R. (2004). Our constructions of trauma: a dialectical perspective. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 17, 201-220. Faidley, A., & Leitner, L. (1993). Assessing experience in psychotherapy. Personal construct alternatives. Fassler, I., Amodeo, M., Gerhard,D. R., Ratliff, D. A., & Lyle, R. R. (2001). Qualitative research in family therapy: a substantive and methodological review. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 27, 261-274. Gottschalk. L. A., & Bechtel, R.J. (2002). PCAD 2000: Computerized psychiatric content analysis and diagnosis. Program and manual. Gottschalk, L.A. & Gleser, G. G. (1969). The measurement of psychological states through the content analysis of verbal behaviour. Berkely: University of California Press. Kelly, G. A. (1955/1991). The psychology of personal constructs. Volume one. A theory of personality (2nd edition). Kelly, G.A. (1955/1991). The psychology of personal contructs. Volume two. Clinical diagnosis and psychotherapy (2nd Edition). Lamb, S. (1986). Treating sexually abused children:issues of blame and responsibility. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 56, 303-307. Langtree, C., Briere, J., & Zaide, L. (1991). Incidence and impact of sexual abuse in a childhood outpatient sample: the role of direct inquiry. Child Abuse and Neglect, 15, 447-453. Leitner, L.M. (1985). The terrors of cognition: on the experiential validity of personal; construct theory. In Bannister, D (Ed). Issues and approaches in personal construct theory. (pp. 83-103). New York, NY: Academic Press. Leitner, L.M. (1988). Terror, risk, and reverence: experienctial personal construct psychotherapy. International Journal of Personal Construct Psychology, 1, 251-261. Leitner, L. M., & Faidley, A. J. (1995). The awful, awful nature of ROLE relationships. In Neimeyer, R. A., and Neimeyer, G. J. (Eds). Advances in personal construct psychology. (pp. 291-314). London: JAI Press Inc. Lusk, R., & Waterman, J. (1986). Effects of sexual abuse on children. In MacFarlane, K., and Waterman, J. (Eds) Sexual abuse of young children. (pp. 101-118) New York, NY: Guilford Press. McCoy, M. M. (1977). A reconstruction of emotion. In Bannister, D (Ed). New perspectives in personal construct theory. (pp. 93-124). New York, NY: Academic Press. Miall,D. S. (1989). Anticipating the self: toward a personal construct model of emotion. International Journal of Personal Construct Psychology, 2, 185-198. Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). An expanded sourcbook. Qualitative data analysis. 2nd edition. Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counselling psychology. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 52, 250-260. Nagel, D.E., Putman, F.W., Noll, J.G., & Trickett, P.K. (1997). Disclosure patterns of sexual abuse and psychological functioning at a 1- year follow up. Child Abuse and Neglect, 21, 137-147. Pennebaker, J. W. (1990). Opening up. The healing power of expressing emotions. Pennebaker, J. W., Francis, M. E., & Booth, R. J. (2001). Linguistic inquiry and word count LIWC2001 Manual. Pennebaker, J. W., Zech, E., & Rime, B. (2001). Disclosing and sharing emotion: Psychological, social, and health consequences. In M. S. Stroebe, W. Stroebe, R. O. Hansson, & H. Schut (Eds.) Handbook of bereavement research: consequences, coping and care. (pp. 517-539). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Polkinghorne, D. E. (2005). Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 52, 137-145. Rime, B., Finkenauer, C., Luminet, O., Zech, E., & Philippot, P. (1998). Social sharing of emotion: New evidence and new questions. The European Review of Social Psychology, 9, 145-189. Sarason, I., Levine, H., Basham, R., & Sarason, B. (1983). Assessing social support: the Social Support Questionnaire. The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 127-139. Viney, L.L., & Caputi, P. (2005). Using the Origin and Pawn, Positive Affect, CASPM, and Cognitive Anxiety content analysis scales in counselling research. Measurement and Evaluation in Counselling and Developemnt, 38, 115-126. Viney, L.L. & Westbrook, M. T. (1979). Sociality: a content analysis scale for verbalizations. Social Behaviour and Personality, 7, 129-137. Viney, L. L., Caputi, P., & Webster, D. (2000). Computerised content analysis scales: their use in personal construct research. Paper presented at the Australasian Personal Construct Psychology Conference. Westbrook, M. T. (1976). Positive affect: a method of content analysis for verbal samples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 44, 715-719. Ystgaard, M., Hestetun, I., Loeb, M., & Mehlum, L. (2004). Is there a specific relationship between childhood sexual and physical abuse and repeated suicidal behaviour? Child Abuse and Neglect, 28, 863-875. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ABOUT THE

AUTHORS Email: hilary.maitland@sesiahs.health.nsw.gov.au  Linda Viney, PhD is a Professional

Research Fellow in Clinical Psychology at the Linda Viney, PhD is a Professional

Research Fellow in Clinical Psychology at the Email: lviney@uow.edu.au Home Page: http://www.uow.edu.au/health/psyc/staff/UOW024981.html |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| REFERENCE Maitland, H. A., Viney, L. L. (2008). Disclosing childhood sexual assault in close relationships: The meanings and emotions women associate with their experiences and their lives now. Personal Construct Theory & Practice, 5, 149-164. (Retrieved from http://www.pcp-net.org/journal/pctp08/maitland08.html) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Received: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

ISSN 1613-5091

| Last update 23 December 2008 |