PC

T&P

| |

PERSONAL CONSTRUCT

THEORY & PRACTICE

|

Vol.6 2009 |

| PDF version |

| Author |

| Reference |

| Journal Main |

| Contents Vol 6 |

| Impressum |

| |

|||||

| |

|||||

| THE HOMELAND OF RECONSTRUCTION: SNAPSHOTS FROM FAËRIE |

|||||

| Carmen Dell'Aversano | |||||

| Pisa University, Italy & Institute of Constructivist Psychology, Padua, Italy |

|||||

|

|||||

| |

|||||

|

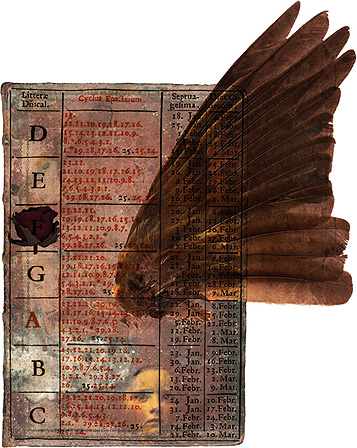

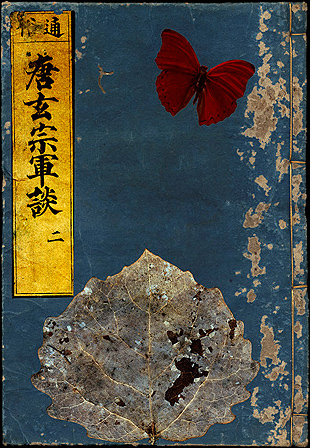

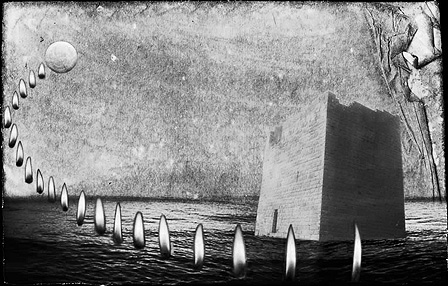

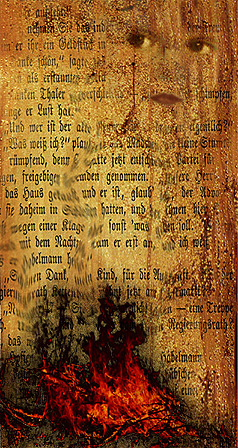

Animal

and plant anatomy, natural history, scientific illustration, ancient books and

images, early photography and alternative photographic processes, randomization and layering, papermaking

and marbling, handwriting, typography and calligraphy, macrophotography and

microscopy, objects manufactured before the invention of plastics, abandoned

buildings and industrial archaeology, kaleidoscopes and magic lanterns,

funhouse mirrors and other distortion devices, myths, opinions, hypotheses and

anecdotes about the underworld, still life, abstractism, expressionism and

children’s book illustration, paedomorphism and androgyny, hybrids and

chimerae, rust, rot, mould and decay. I believe that, like construing in general, making art is a collaborative process between the person and the world. A part of the world enters into a special relationship with the person, and the result is art. It is a bit like the process by which pearls are produced by oysters, except that it is a lot messier and more unpredictable: sometimes the result is a pearl, sometimes rubbish, and most times one cannot be sure and keeps oscillating between the two poles of the pearl/rubbish construct until the piece is destroyed or forgotten. Just as not any material can be used in pearl-seeding (even though I can't help wondering what pearls produced around leaves or feathers or noodles would look like!) not all parts of the world can do the trick for all persons. Indeed, in my experience, very few parts of the world work for me. It's been the same ones for as long as I can remember; occasionally I come across a new one, but it feels not so much as adding something to the list as like coming across an item that I had accidentally forgotten, and whose obviousness stares me in the face much like a food one is accustomed to eating and can't do without will pop out to one in a supermarket even though one may have forgotten to include it in a shopping list. My list, which is the only piece of personal information available on my website (www.shadowsoftheworld.com) is the epigraph to this paper. These are the things that enchant me. These are the things I can never stop looking at and having visions about. These are the things that make me make art. Why these things? What do they have in common? What do they tell me about myself? As long as I can remember, I have been plagued by a violent uneasiness about the world as it is. My earliest and most constant feelings were of being in the wrong place, surrounded by the wrong people and the wrong objects; and this sense of wrongness was above all aesthetic: I was much more keenly and continuously aware of how physically unpleasant, depressing and disappointing the things and people that I came in contact with were than I was of callousness, phoniness and injustice. In my privileged childhood in a rather well-to-do urban professional family, I found absolutely everything around me unbearably ugly: the colours of my toys, the feel of my clothes against my skin, the voices and accents of the adults who talked to me. No, not so much ugly as wrong: my perception of ugliness was indissolubly tied to a very strong, even though as yet nebulous, sense of the way things should have been and were not. Everything around me was totally, painfully wrong; but somewhere something must, I felt sure, be right. I must only keep looking for it. And look for it I certainly did, with an inventiveness and determination that would now probably earn me an ADHD label, and the medication to go with it. As soon as I was able to move about (which was remarkably early), I started getting into trouble; I did it methodically, predictably, almost conscientiously, the way one would go about performing one's tasks in a job one considers important. Three reasonably efficient adults (my nanny, the housekeeper and my grandmother, who lived with us) had their hands full trying to keep me from mischief; they did not usually succeed. My grandmother had noticed that the only thing that kept me quiet were stories; while I was listening to a story I stopped trying to look for physical clues of, or means of escape to, the right place, because I felt I already was there.[1] But surely nobody could be expected to spend their life providing me with the staggering amount of narrative needed to keep me reliably in check. Then, when I was about three years old, out of sheer desperation, my mother came across the solution which changed my life. She taught me to read.[2] I have always been unable to comprehend the stigma attached to ‘escapist’ literature. To me, from well before I became acquainted with the word, literature has always been a means of escape. Here everything was wrong; there, everything was right. I could get from here to there simply by opening a book and allowing the words to unfold within my mind as in the Japanese game described by Proust,[3] transforming into places, people, events and objects. This miracle, which repeated itself several times a day, and which I came to rely upon (though I could never grow accustomed to it: I still have not), taught me, when my grasp of language was still primitive and my knowledge of the world minimal, something which is vastly more basic and profound than any highly moral or politically progressive ideal could ever be, because ontology is, by definition, more basic and profound than ethics: that "another world" is not only, as the World Social Forum slogan puts it, "possible", but that it is real. The first narratives that I came across, and that I kept demanding from my exhausted adult caregivers, as well as most of the ones contained in the books I devoured during my first voracious years as an autonomous reader, were indeed about another world: they were fairy stories: Fairy-stories are [...] stories about Fairy, that is

Faërie, the realm or state in which fairies have their being. (Tolkien, 1945, p. 42) This was a happy, I would almost say a providential, coincidence: I remember reacting very coldly to books which did not belong to this genre, and a higher proportion of them in my first experiences might well have turned me off reading altogether, with momentous adverse consequences on my life to this day. If, as my present adult, reasonably sophisticated self, I wonder why fairy stories appealed to me so exclusively, I am reminded of Freud's warning about the precariousness of realism and rationality, forever labouring under the threat of older and more rewarding modes of thought.[4] In my experience, though, the appeal of the revolt against realism embodied in even the simplest fairy story or the least accomplished Surrealist painting has nothing to do with the "saving of psychic energy" which Freudian theory, in agreement with its dynamic premises, sees as its main source: the task of imagining another world is not less complex and onerous in aesthetics than it is in politics; indeed, the line between the two fields may be blurry and ultimately illusory: [T]he effect of this

book [The Master and Margarita] was really fantastic. There’s an

expression “out of this world.” This book was totally out of the Soviet world.

The evil magic of any totalitarian regime is based on its presumed capability

to embrace and explain all the phenomena, their entire totality, because

explanation is control. Hence the term totalitarian. So if there’s a book that takes you out of this totality of things

explained and understood, it liberates you because it breaks the continuity of

explanation and thus dispels the charms. It allows you to look in a different

direction for a moment, but this moment is enough to understand that everything

you saw before was a hallucination (though what you see in this different

direction might well be another hallucination). The Master and

Margarita was exactly this kind of book

[...]. Solzhenitsyn’s books were very anti-Soviet, but they didn’t liberate

you, they only made you more enslaved as they explained to which degree you

were a slave. The Master and Margarita

didn’t even bother to be anti-Soviet yet reading this book would make you free

instantly. It didn’t liberate you from some particular old ideas, but rather

from the hypnotism of the entire order of things. (Pelevin, 2002) In PCP (Personal Construct Psychology) terms, the difference Pelevin so memorably describes between Solzhenitsyn’s books and The Master and Margarita is the difference between slot-rattling and reconstruction. And this difference is as important in politics as it is in aesthetics, and in both (indeed, in all) fields it is a consequence of ontological premises: slot-rattling acquiesces in the definition of reality implicit in a given construct, and confines its activity to oscillating between its poles; reconstruction moves "out of the world" defined by a given construct system, "takes you out of [the] totality of things explained and understood [within that construct system], [and] liberates you because it breaks the continuity of explanation and thus dispels the charms". Once one comes to terms (as one must inevitably do in the very first stages of becoming involved with PCT [Personal Construct Theory]) with the fact that all construct systems have totalitarian qualities and implications, that they all necessarily possess and enact an "evil magic [...] based on [their] presumed capability to embrace and explain all the phenomena, their entire totality, because explanation is control", one cannot but recognize the inherently subversive drift of all attempts to question the realist ontology and gnoseology, and their significance for constructivist theory and practice. To me, even when I was too young to be able to read them myself (let alone formulate the thought), the invariable and ever-changing meaning of each and every fairy story was reconstruction. The intrinsically subversive nature of all fairy stories (even of the comparatively tame ones which my well-meaning grandmother told me when I was yet unable to get my own daily fix) is very clearly spelt out by the most profound and enlightening theorist of the genre: I

have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and

since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of

scorn or pity with which “Escape” is now so often used [...]. Why should a man

be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or

if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers

and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the

prisoner cannot see it. [...] The escapist is not so subservient to the whims of

evanescent fashion as [his] opponents. He does not make things (which it may be

quite rational to regard as bad) his masters or his gods by worshipping them as

inevitable, even “inexorable.” And his opponents, so easily contemptuous, have

no guarantee that he will stop there: he might rouse men to pull [them] down

[...]. Escapism has another and even wickeder face: Reaction. (Tolkien, 1945, p. 77) The derogatory label which is commonly used to dismiss all aesthetic attempts to question realism is developed by Tolkien into a refutation of its most basic ontological premises which is no less coherent and radical for being expressed in figurative language. [5] Commonly shared reality, with its ontological, gnoseological and perceptual constraints, is a "prison", and "the world outside", that is, Faërie, is not only "real" but is "home": wanting to escape from one to the other does not demonstrate an inability to cope with reality but, quite on the contrary, an accurate and lucid awareness of its actual nature. Whatever they may ostensibly be about, what all fairy stories do is affirm the existence of a "world outside", a world which is "real" even though "prisoner[s] cannot see it". From my earliest childhood, this is what I always knew, believed and felt. This is why I liked – this is why I needed... – fairy-stories. Aside from these ontological remarks, couched in the oblique language of metaphor, Tolkien explicitly refrains from any description or definition of Faërie: I will not attempt to define that [the nature of

Faërie], nor to describe it directly. It cannot be done. Faërie cannot be

caught in a net of words; for it is one of its qualities to be indescribable,

though not imperceptible. (Tolkien, 1945, p. 42) My own perception of Faërie has, from the very first inklings, been very keen indeed, and has given me a clue to its true nature. To me Faërie is the place where everything is right; and the impossibility to describe it in a way that will preserve and convey its true meaning is a corollary of this definition, for of course the construct of right is a personal construct, and a description of my own Faërie would probably bore, frighten or even disgust other people, just as a description of theirs would in all likelihood be uninteresting or unintelligible to me. [6] From my seminal encounters with fairy stories, to me art, in whatever medium, has always been about Faërie. And when I started making art I was moved by the impulse, indeed the need, to document my encounters with fragments of Faërie. What the subjects of my photographs, the objects that I assemble in my montages, the "interests" listed in the self-description I quoted as an epigraph have in common, despite their bewildering diversity, is the fact of having been recognized as belonging not to this world but to my own, to the "right" place that I have been trying to escape to for as long as I have been me. These encounters can best be defined by the word enchantment. According to Tolkien, enchantment is the state in which humans are incorporated in Faërie: Faerie contains many things besides elves and fays,

and besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants, or dragons: it holds the seas, the

sun, the moon, the sky; and the earth, and all things that are in it: tree and

bird, water and stone, wine and bread, and ourselves, mortal men, when we are

enchanted. (Tolkien, 1945, p. 42) I have never had this precious experience. But I have felt many, many times, so often indeed as to have come to depend upon it, and to rely upon it for my sanity and survival, that some objects, as disparate as a song by Thomas Campion, a dead lizard picked up during a walk near my home, or an old photograph unearthed on eBay, can perform the less conspicuous but not less miraculous feat of making not me present in Faërie, but Faërie present in me: of altering the object, and thus the state, of my consciousness, focusing it on something which is at the same time outside, and infinitely more real than, ordinary reality, which is always potentially present as the defining component of my innermost being, but which can be made actual only by the blessed fatality of a chance encounter with a particular object In this sense too, every contact with Faërie is a constructivist experience: Je trouve très raisonnable

la croyance celtique que les âmes de ceux que nous avons perdus sont captives

dans quelque être inferieur, dans une bête, un végétal, une chose inanimée,

perdues en effet pour nous jusqu'au jour, qui pour beaucoup ne vient jamais, où

nous nous trouvons passer près de l'arbre, entrer en possession de l'objet qui

est leur prison. Alors elles tressaillent, nous appellent, et sitôt que nous

les avons reconnues, l'enchantement est brisé. Délivrés par nous, elles ont

vaincu la mort et reviennent vivre avec nous. (Proust 1913, I p. 43-44) ("I find the Celtic belief to be very reasonable that the souls of those we have lost are imprisoned within some inferior being, in an animal, in a plant, in an inanimate thing, lost in effect to us until the day, which for many never comes, when we chance to pass the tree, to come in possession of the object which is their prison. Then they are startled, call to us, and as soon as we recognize them, the spell is broken. Freed by us, they have vanquished death, and come back to live with us." My translation.) To my knowledge, this passage is the best literary representation of the relational ontology which is the hallmark of constructivism.[7] In order to come back to life the souls of the dead need to enter into a relation with those who are missing them; their being "objectively there" in the "être[s] inférieur[s]" where, according to all tenets of realism, they are trapped, is not enough, just as the action of the person who misses them, which in an idealistic perspective is enough to found a world and to give existence to anything within it, also comes short of the mark; the only thing that will do the trick is a dialogue between two parties to which the labels subject and object no longer apply ("elles tressaillent, nous appellent"), because the healing activity which performs the miracle is split equally between the two ("Délivrés par nous, elles ont vaincu la mort", my italics). What I have said so far can explain most of the defining characteristics of my artwork, thematically, stylistically and technically. To me Faërie is real; indeed, its reality is far more intense and meaningful than that of shared everyday mundane and profane experience. As an obvious consequence, ever since I realized that I could attempt to portray it visually, I have gravitated towards the most painstakingly realistic technical means available: I started out with photography, went on to macrophotography, from there to montage, incorporating real, three-dimensional objects in my artwork, and then discovered the scanner. This marked a momentous turning point in my artistic process. Placing any reasonably flat and relatively small object on the scanner plate yields a hypnotically, almost infinitely detailed result: at high resolutions the scanner acts as a low-magnification microscope, and the complexity and detail of the images it produces cannot be compared to anything that is visible with the naked eye. To me, this is a convincing likeness of the "reality beyond reality" of Faërie, of its inexhaustibility, of its infinite capacity for wonder and of its particular brand of beauty, which is never reassuring or predictable; which always leads one beyond familiar territory and constructs, into the uncanny, the threatening, the shocking; and on to reconstruction. O see ye not yon narrow road So thick beset wi' thorns and briers? That is the path of Righteousness, Though after it but few inquires. And see ye not yon braid, braid road That lies across the lily leven? That is the path of Wickedness, Though some call it the Road to Heaven. And see ye not yon bonny road That winds about yon fernie brae? That is the road to fair Elfland, Where thou and I this night maun gae. [...] O they rade on, and farther on, And they waded thro rivers aboon the knee, And they saw neither sun nor moon, But they heard the roaring of the sea. It was mirk mirk night, and there was nae stern light, And they waded thro red blude to the knee; For a’ the blude that’s shed on earth Rins thro the springs o that countrie. [8] But as relevant to my poetics is the complete malleability of the images a scanner produces. A reasonable competence in the use of a graphics program makes it possible to tweak and adjust all parameters, and thus to edit out all traces of accidental mundanity from found objects, making them more truly themselves, that is, more truly of Faërie; and also to make them more compatible with one another, highlighting, by use of various visual cues, their being of one place and belonging together. Digital imaging also makes it possible to combine images from various "real" sources into objects which do not exist in everyday reality, but whose portrayal respects, indeed exceeds, the time-hallowed conventions of realism which play such a major part in our construction of reality and in the faith we accord to it.[9] Such compositing, from my earliest experiments with montage to my present involvement with digital graphics, is a major feature of my style. In PCP terms, I experience making art as a process of loosening, with as little tightening as is compatible with the completion of a Creativity Cycle. (Since in other areas I am a seriously loosening-challenged person, this is one major way in which making art helps me preserve some sort of balance.) The materials I assemble are connected by a deep resemblance which makes it possible for me to combine them almost at random and to almost always come up with a result which I find both pleasant and meaningful: surprisingly often my pieces seem to almost "fall into place" as they would not if I were not working with the "right" stuff to begin with. The computer has added unimaginable depth to my loosening by presenting me with innumerable levels of randomness: anybody even vaguely familiar with digital graphics knows that endless versions of the "same" work can be produced by infinite variations on all imaginable parameters, and probably at least suspects that the most enchanting possibilities are the result not of meticulous planning but of random playfulness. This feature is deeply coherent with the role reconstruction plays as the core construct of my poetics: random processes, from those involved in ancient crafts like paper marbling to those made possible by layer compositing in Photoshop, enable us to escape from the stable tracks of our usual constructs into the freedom of almost complete lack of anticipation. In my artistic construct system, randomness is reconstruction embodied. But of course technique, style and process are subordinate to a poetics, and only meaninfgul within it.[10] The purpose of my work, the poetic aim to which all stylistic and technical choices are subservient, is to convey my experience of Faërie. This leads us to the question Tolkien thought could not be answered: what is Faërie like? As in many other fields, PCT offers a way out of this apparently insoluble issue by a radical reformulation. Since Faërie is a personal construction (more specifically, a personal construction of the "right place"), the question to ask is not "What is Faërie like?", but "what is Faërie like for me?" At the same time, though, this insistence on the personal construction of Faërie would seem to contradict the decision to make one's art publicly available, as I do through my website, exhibitions and the selling of works. Why should my construction of Faërie interest or appeal to anybody else? Indeed, how could it? While I do not assume that it should, a fair number of people have been kind enough to tell me that it actually does. From a PCT viewpoint, this is a fairly surprising phenomenon; I believe that some technical and thematic features of my work can go some way toward explaining it. My visions are composites of objects and images from an extensive collection I have been adding to for several decades; they convey the impressive level of detail made possible by digital technology, but, as well as being hypnotically detailed, they are also details: they do not display sweeping landscapes or grand scenes, but focus on the small and the marginal: the curtain is not lifted but pushed aside by a mere handbreadth. My works do not represent another world but only allude to it; and allusions are, by definition, ambiguous: in order to mean anything at all, they require a high degree of involvement and collaboration from the viewer. By refraining from compiling a complete illustrated guidebook to my Faërie but focusing instead on the unprepossessing and the easily overlooked, I aim to lead my viewers to start a journey towards their own "right place", a journey facilitated but by no means exhausted by their perusal of some details of mine.  Ala su libro

Libro

cinese azzurro Although my chosen mediums are visual, my experience of Faërie is not a primarily visual one. To me, visual stimuli are cues which are valuable for their ability to call up non-visual experiences and constructs. In their detailed specificity, the objects listed in the epigraph are subordinate rungs in the ladder which leads to Faërie. If for a moment I try to escape their hypnotic charm in order to perform some simple logical operations with them, I realize that their seeming randomness points to the resolution of a surprisingly clean-cut set of dichotomies which are ubiquitous in our culture but with which I have always felt deeply uncomfortable. Whatever else may be true about Faërie, these ways of carving up experience do not exist there; my work is an attempt at the resolution of these dichotomies, at the reconstruction of these core constructs. Here they are, with a few words of explanation. Real - Unreal Surreal From long before I knew anything about PCT, I have always felt the distinction between real and unreal to be the most powerful and most unfair instrument of repression of personal construction, individuality and, ultimately, identity. Indeed, the reconstruction of this dichotomy is of such momentous importance in my definition of the ‘right place’, and in explaining its ultimately constructivist nature, that I have devoted a whole paper (Dell'Aversano, 2008) to exploring its role in far better artists than I. One major aspect of this process of reconstruction in my own work has to do with books: to many people (certainly to those suspicious of "escapist" literature) books are the guilty embodiment of the unreal; but at the same time books are tangible three-dimensional objects, as real as chairs or fireplaces. In my work everything having to do with the materiality of books, from age-stained pages to typography and calligraphy to ancient covers of tooled leather to the irregular margins of torn pages has always played a major role as the emblem of their two-faced nature, halfway between the real and the unreal, and thus beyond both.  Torre-Mare Mundane - Supernatural Wonder The best explanation I can find for this is Flaubert's "for a thing to be interesting, it is enough to look at it for a long time". Wonder is the core feeling I would like to evoke with my art; I feel that hyperrealism and surrealism are equally effective ways to experience it; indeed, wonder as I understand it is the realization that one's construct system is equally inadequate to account both for the mundane and for the supernatural; that, as Haldane would put it, the world is not only queerer than we imagine, but queerer than we can imagine. Past - Present Timelessness Ever since I became aware of history, my feeling of being in the wrong place was explained by the perception of being in the wrong time. To me, the chasm separating the present from the past, the irretrievability of time gone by, has always felt like a grotesque deception (that my favourite book should be A la récherche du temps perdu is not exactly a coincidence): in my experience, the past with which I became familiar through the study of history, literature and art was vastly more present than the present, while the present, with its lack of intensity and concentration, felt like a watered-down version of the past, much like a TV soap opera with its phony realism feels like a watered-down version of real life. In Faërie, all the pasts of all the cultures that I have studied and loved, as well as many alternative ones that were never realized in actual history, coexist in blessed timelessness. Life - Death Transcendence This is an extreme development of the previous construct. The opposition between present and past is often unwittingly framed as "we, the living" vs. "they, the dead". We are where progress has led our species; we know more, can do more, and can look with pity and contempt down upon the primitive savages who came before us. We cannot imagine being superseded any more than a child of three can imagine being ten. The dead are always wrong, especially since they cannot speak from themselves and, even if they could, nobody would understand them anyway. It does not take a profound knowledge of PCT to perceive that the game between the living and the dead is badly rigged, which in itself does not reflect too well on the living, who are responsible for the rigging. But of course the purpose of the living in setting up such an impassable barrier is not to be unfair to the dead but to forget that, very soon, they will be dead too. Thus the construct Life-Death threatens to resolve itself into one of its poles. If we wait long enough, only Death remains. Unless, that is, we accept the possibility that the Life-Death dichotomy can be resolved in a completely different way, one which does not rely upon the same axes to articulate meaning. If the dead were once the living, and the living will soon be the dead, then the difference between them, of which we make so much, is ultimately futile and meaningless. We can experience a closeness and an empathy with the dead which we normally would find extremely threatening. The place where this closeness happens is beyond the Life-Death construct. For want of better words, I call it Transcendence.  Monachicchio For me the reconstruction of this construct is fraught with ethical implications. I feel that the dividing line our species has drawn to separate itself from other sentient beings is not only intellectually fraudulent but at the root of all ethical evil. Every abuse that has ever been performed by humans on other humans has been justified by a process of "dehumanization", that is, by pushing them on the other side of the line; if the line no longer existed, much of what makes the earth a place of misery both for humans and for animals would become unthinkable. The gnoseological implications, though not as evident, are even more important: to me, because of their irreducible otherness, of their fresh and incomprehensible way of looking at the world we share with them, of the bewildering abilities and deficits which make them both superior and inferior, and thus equal to us, animals are the living embodiment of PCT. But as important as any ethical or gnoseological considerations is the fascination I have always felt for the particular brand of beauty which to my eyes is their exclusive prerogative: uncanny, sometimes abstract, and truly alien. Male - Female Androgyny This is a somewhat tamer version of the previous one. I have always found everything having to do with gender roles alternately stifling and laughable (well, actually, most often both at the same time...). To me, "virile" men and "feminine" women tend to look and sound like caricatures, and to be quintessentially unattractive: my perception of beauty clamours for a reconstruction of the male-female construct as loudly as my ethical and political convictions. Monstrosity - Prettiness Beauty Denn das Schöne ist nichts als des Schrecklichen Anfang, den

wir noch grade ertragen,und wir bewundern es so, weil es gelassen verschmäht uns zu zerstören. Rilke, Duineser Elegie I (For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror, that we are

still barely able to bear,and we revere it so, because it calmly disdains to destroy us.) (my translation) One is reminded in this connection of a story concerning Kobori-Enshiu. Enshiu was complimented by his disciples on the admirable taste he had displayed in the choice of his collection. Said they, "Each piece is such that no one could help admiring. It shows that you had better taste than had Rikiu, for his collection could only be appreciated by one beholder in a thousand." Sorrowfully Enshiu replied: "This only proves how commonplace I am. The great Rikiu dared to love only those objects which personally appealed to him, whereas I unconsciously cater to the taste of the majority. Verily, Rikiu was one in a thousand among tea-masters." (Okakura, 1906, p.40).  Bränt Barn ENDNOTES [1] When, quite recently, I started reading extensively on the topic of NOSCs (non-ordinary states of consciousness) I realized that my experience of literature and art in general from earliest childhood to this day bears an uncanny resemblance, in structure if not in content, to that of various ‘psychonauts’. This should not be surprising: the purpose of art (whether it be literature, music, painting or photography, or film, is to alter the consciousness of the viewer not only, as it is obvious, by making him conscious of a reality beyond his immediate surroundings, but also by making him differently conscious. An exploration of this phenomenon in Kellyan terms would take up a whole paper (and not a short one); a faithful phenomenological description can be found in Stevie Smith's poem "Deeply Morbid" (Smith 1950 pp.296-298): Close upon the Turner pictures Closer than a thought may go Hangs her eye and all the colours Leap into a special glow All for her, all alone All for her, all for Joan. [...] The spray reached out and sucked her in It was a hardly noticed thing That Joan was there and is not now (Oh go and tell young Featherstonehaugh) Gone away, gone away All alone. She stood up straight The sun fell down There was no more of London Town She went upon the painted shore And there she walks for ever more Happy quite Beaming bright In a happy happy light All alone. [2] She used the method outlined most recently in Doman & Doman (2005). [3] "Et comme dans ce jeu où les Japonais s'amusent à tremper dans un bol de porcelaine rempli d'eau, de petits morceau de papier jusque-là indistincts qui, à peine y sont-ils plongés s'étirent, se contournent, se colorent, se différencient, deviennent des fleurs, des maisons, des personnages consistants et reconnaissables [...]" Proust (1913 I, p. 47). ("And like in that game where the Japanese amuse themselves by immersing in a porcelain bowl filled with water some small shapeless pieces of paper which, as soon as they are drenched, spread, and acquire different shapes and colours, becoming flowers, houses, consistent and recognizable characters [...]" my translation.) [4] This is a Leitmotiv of Freudian thought, and a comprehensive list of occurrences would almost be equivalent to an index of the Standard Edition. Two among the clearest and most accessible are to be found in lectures 23 and 30 in Freud (1917) and (1930) respectively. [5] This figurative cover allows Tolkien to affirm an unwavering belief in the existence of a reality with respect to which present-day shared consciousness is nothing more than a "prison", while at the same time continuing to express a distaste of Surrealism in aesthetics ("[t]here is, for example, in surrealism commonly present a morbidity or un-ease very rarely found in literary fantasy. The mind that produced the depicted images may often be suspected to have been in fact already morbid; yet this is not a necessary explanation in all cases. A curious disturbance of the mind is often set up by the very act of drawing things of this kind, a state similar in quality and consciousness of morbidity to the sensations in a high fever, when the mind develops a distressing fecundity and facility in figure-making, seeing forms sinister or grotesque in all visible objects about it") and of dream and hallucination in ontology ("[m]any people dislike being “arrested.” They dislike any meddling with the Primary World, or such small glimpses of it as are familiar to them. They, therefore, stupidly and even maliciously confound Fantasy with Dreaming, in which there is no Art; and with mental disorders, in which there is not even control: with delusion and hallucination") which I, for one, cannot help but find rather puzzling. [6] Tolkien himself must have been well aware of this risk, since he refrained from giving a full description of his own Faërie, but devoted his published works to narratives of events taking place there, including only enough description to make them intelligible and enjoyable. [7] For a detailed explanation of this concept, which provides a much-needed way to discriminate between the bewildering varieties of constructivism on one hand and all other gnoseological positions on the other, readers are very much encouraged to refer to Stojnov & Butt (2002). [8] I have always felt it to be uncannily appropriate that this ballad (Thomas the Rhymer) should be the only literary text that Tolkien quotes at any length in his essay on Faërie. Very rarely have I come across (outside technical constructivist literature) such a clear and convincing representation of reconstruction as the repudiation of both poles of a given construct (yon narrow road / yon braid, braid road) and at the same time as something intrinsically threatening in the highest degree (And they saw neither sun nor moon, / But they heard the roaring of the sea. [...]And they waded thro red blude to the knee). This is in my opinion as good evidence as any that the intermediate position between two poles is a genuine instance of reconstruction; for an in-depth exploration of this issue one should of course refer to Ugazio (1998, p. 70). [9] The relationship between realism in aesthetics and in gnoseology, and the subversion of both in surrealism, is more fully explored in Dell'Aversano (2008). [10] The relationship between poetics, style and technique in artistic creativity and in its development is the subject of Dell'Aversano, in press. [11] This version of the wording of "Thomas the Rhymer" is taken from the Steeleye Span recording where I first encountered it: Now We are Six, Chrysalis Records 1974. | |||||

| |

|||||

| REFERENCES | |||||

| Dell'Aversano,

C. (2008). Beyond dream and reality: Surrealism as reconstruction. Journal of Constructivist Psychology,

21, 328-342. Dell'Aversano, C. (in press) Exploring aesthetic constructs: How likes and dislikes define a style. Journal of Constructivist Psychology Doman, G. & Doman, J. (2005). How to teach your baby to read. Wyndmoor, Pennsylvania: The Gentle Revolution Press. Freud, S. (1930). New introductory lectures on psychoanalysis. London: Hogarth Press. Okakura, K. (1906). The book of tea. Pelevin, V. (2002). Viktor Pelevin interviewed by Leo Kropywiansky, Bomb, 79 Spring 2002, http://www.bombsite.com/issues/79/articles/2481 Proust, M. (1913). À la recherche du temps perdu, édition publiée sous la direction de Jean-Yves Tadié, Paris: Gallimard 1987-1989 (original edition 1913 onwards), Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, voll. I-IV. Rilke, R. M. (1908-1926). Poesie II , ed. G. Baioni, Torino: Einaudi-Gallimard, (1995), p.54. Smith, S. (1950) Harold's leap in The collected poems of Stevie Smith (pp. 225-300) London: Penguin. Stojnov, D. & Butt, T. (2002). The relational basis of personal construct psychology. In R. A. Neimeyer & G. J. Neimeyer (eds.) Advances in Personal Construct Psychology (pp.81-112). Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group/Praeger. Tolkien, J. (1945). On Fairy-Stories. In C.S. Lewis (ed.) Essays Presented to Charles Williams (pp. 38-90). London: Oxford University Press. Ugazio, V. (1998). Storie permesse, storie proibite. Polarità semantiche familiari e psicopatologie. Torino: Bollati Boringhieri. | |||||

ABOUT THE

AUTHOR Carmen Dell'Aversano: Biographical information from the mundane to the indiscreet is liberally

scattered throughout this paper. I should maybe add that most of my time is

spent not making art but in research (mainly in literary theory and criticism

and PCT) and in political activism in the field of animal rights. Carmen Dell'Aversano: Biographical information from the mundane to the indiscreet is liberally

scattered throughout this paper. I should maybe add that most of my time is

spent not making art but in research (mainly in literary theory and criticism

and PCT) and in political activism in the field of animal rights.Email: aversano@angl.unipi.it Home Page:http://www.shadowsoftheworld.com/ |

|||||

| |

|||||

| REFERENCE Dell'Aversano, C. (2009). The homeland of reconstruction: Snapshots from Faërie. Personal Construct Theory & Practice, 6, 3-14, 2009 (Retrieved from http://www.pcp-net.org/journal/pctp09/dellaversano09.html) |

|||||

| |

|||||

| Received: |

|||||

| |

ISSN 1613-5091

| Last update: 20 March 2009 - Portrait: ICP-Padova |