PC

T&P

|

|

PERSONAL

CONSTRUCT

THEORY & PRACTICE

|

Vol.7 2010 |

| PDF version |

| Author |

| Reference |

| Journal Main |

| Contents Vol 7 |

| Impressum |

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| OVERLAPPING

INTELLECTUAL COMMUNITIES AT WORK: EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH IN THE REALM OF PERSONAL CONSTRUCT PSYCHOLOGY AND PHENOMENOLOGY |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Britt Marie Apelgren | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Department

of Education, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| INTRODUCTION The question why educational research within personal construct psychology (PCP) needs an infusion of other connected theories and methods has been much discussed for decades. Different scholars have highlighted commonalties between closely related theories and in this paper I will argue for the development of PCP-based educational research using phenomenological analytical tools. The main reason for the proposal of an extended research base for PCP probably lies in the fact that ‘constructivism’ is a broad term encapsulating several different theories sharing the assumptions and commonalities of ‘lived experiences’ and ‘personal meaning’ of individuals. Recently, Personal construct psychology (PCP) researchers have highlighted connections to other constructivist theories, such as radical constructivism and social constructivism (Butt, 2006; Fransella, 2006; Raskin 2006; Warren, 2004), as well as to different philosophical theories, mainly phenomenologogy (Apelgren 2001, 2003; Butt 1997, 2003, 2004; Warren, 1998). Further, Raskin (2002:12) argues that “there is a great deal of room for cross-fertilization among the various constructivist psychologies”. In constructivist educational research the discussion of constructivism as a meta-theory is by no means new. In 1981, Pope & Keen outlined the commonalities between social phenomenology and PCP, and both Pope (1995) and von Glasersfeld (1991) have highlighted commonly shared notions within different constructivist educational research and the pluralistic nature of such views. Other important issues concerning PCP theory and education, namely learner empowerment, critical reflection and lifelong learning in relation to Kelly’s theory, and the notion that all theories are temporary constructions open to experiences and change when a person encounters new events, are all dealt with in Pope & Denicolo (2001). In this respect education, as well as educational research, has to do with personal meaning and meaning making. Teachers need to be able to illuminate their learners’ understanding of specific matters in the subjects they are teaching, whilst the researcher’s task is to bring to light participants’ personal meanings of particular events and situations. It is likewise interesting to note that, within the history of educational psychology, there has been a constant move to issues such as human learning and development and away from psychology applied to education with, instead, a focus on research on processes of teaching and learning and, not infrequently, to where such processes actually take place, namely in classrooms where individual pupils, both alone and together with their peers and teachers, are engaged in learning. In short, research in the field of education is, by nature, interpretive and constructive or, if so preferred, can be described using the philosophical term ‘hermeneutic’ (Hilgard, 1997). For many years, the connections between and commonalities within the two approaches, PCP and phenomenology, have intrigued me (Apelgren 2001, 2003, 2005). As seen above, this interest is in no way unique and several others within PCP have written about this relationship, although not exclusively in relation to education and educational research. In The introductory line of the title “overlapping intellectual communities at work” is borrowed from Phillips’ contribution on philosophical perspectives in Handbook of Educational Psychology (1997: 1005). Here he refers to psychology and philosophy as disciplines that have the potential to gain much from each other. This is in line with the constructivist idea that we share, develop, grow and benefit from being open to other perspectives, which is the paramount consideration and guiding light for my explorative investigation. In conducting this work, three aspects will be in focus. First, by examining the ideas of a number of well-known phenomenologists and by tracing the developments of phenomenology in different directions, a brief history of phenomenology will be provided. Second, along with the discussion of key concepts within phenomenology, the importance of intentionality, temporality and lived experience will be discussed. Finally, and most importantly, phenomenology will be discussed and related to personal construct psychology and educational research. Ultimately, the aim is to explore whether and in what ways, these two theories can complement one another and, more importantly, serve as a theoretical basis for different kinds of constructivist educational research. In addition, examples from my own research will be given. PHENOMENOLOGY AND PERSONAL CONSTRUCT PSYCHOLOGY One important initial question that needs to be addressed concerns the nature of phenomenology and the ways in which it differs from Personal Construct Psychology. What, then, could be more appropriate than to start by comparing the two theories from the writings of their fathers; Husserl (1913/1931) and Kelly (1955/1963)?

In the chart above, the main differences are considered. In the classic philosophy of phenomenology the knowledge base is logic, i.e. thinking and, in particular, the researcher’s (or the philosopher’s) own thinking, as compared to the empirical knowledge base of PCP where the participants’ thinking and experiences are in focus. The aims of research also differ in classic phenomenology and PCP. Whilst in phenomenology the essence or the absolute knowledge of a phenomenon is the ultimate research objective, in PCP the focus is on the individual’s experiences of a phenomenon. As with constructivism, there are differences within the theory of phenomenology between different ‘schools of phenomenological studies’, and between what Patton (1990) calls ‘general phenomenological perspective’ (philosophy or theoretical background to justify methods) and what today is more commonly known as ‘phenomenology of practice’, more empirical phenomenological studies. In the sections that follow, those differences will be discussed. Different schools of phenomenological study and some developments within PCP The variance between different schools of phenomenology can perhaps best be described as a divergence between classic phenomenology and empirical phenomenology. In many ways this difference is best in evidence in definitions of the concept of ‘essence’. Husserl’s definition of essence is very close to the notion of ‘concept’ (Husserl 1913/1931, p.90). In The Concise Oxford Dictionary (1995) ‘concept’ is described as: (1) a general notion, an abstract idea or (2) a philosophical term for a group or class of objects formed by combining all their idea and aspects. Husserl has called this the ‘whatness’ of a thing. Those who define ‘essence’ in this way seem to regard intuition and logical thinking as the only way to reach the knowledge of essence, i.e. logic as the only knowledge base. There are, however, other definitions of ‘essence’. Some phenomenologists (for example van Manen, 1990) make a distinction between ‘fundamental essence’, like Husserl’s essence, and ‘empirical essence’. By introducing empirical essence, there is a resemblance and proximity to individuals’ experiences of phenomena. Thus, it is also closer to empirical research disciplines, such as PCP and phenomenography, i.e. empirical approaches that take their starting point in individuals’ lived experiences. The above differences have, on the one hand, led to a strong move towards empirical data and description as well as the interpretation of data. Hermeneutic phenomenology can be seen as one branch of that direction. Hermeneutical phenomenology is described by van Manen in his book Researching Lived Experience in the following way: Phenomenology is

not mere speculative inquiry in the sense of unworldly reflection. Phenomenological

research always takes its

point of departure from lived experience or empirical data. /---/ Thus,

phenomenology consists in mediating in a personal way the antinomy of

particularity (being interested in concreteness, difference and what is

unique)

and universality (being interested in the essential, in difference that

makes

the difference).

(van

Manen, 1990, p. 22-23).

Not all phenomenological research may so directly be connected to that of educational research in PCP, particularly not those which are based solely on logic and with the idea that the essence is an absolute and not an empirical essence. Van Manen’s position, though, puts emphasis on empirical data and interpretation of data, which gives this approach to phenomenology a position in line with other empirical approaches, such as for example PCP. Considering the aim of this article, one obvious question to ask would be whether it is indeed possible to combine phenomenology and PCP. As with most research, the answer must be that it depends on how we as researchers regard our research – whether we are ready to embrace research that is more eclectic in nature. For the more eclectic constructivist researcher, the answer will most probably be ‘yes’, it is possible to combine or develop certain aspects as long as this does not interfere with the general theoretical assumptions of the approach. For theoretical purists, both within phenomenology and PCP, it is however difficult to see a bridge between the two positions. The tension between the ‘empirical’ and the ‘logical’ is also evident in the Nordic debate about the aim and outcomes of phenomenological educational research (Bengtsson et al, 2000; Dahlin, 2000). Here the focus is on the classification of phenomenological research in education as subjective or objective, and as either individual or collective. The complex question of phenomenology as a descriptive psychology is discussed by Scanlon who, referring to Husserl’s Logic Investigations, states that: “such a project of reflecting upon conscious experience fit within the general scope of what still counted among philosophers as a form of descriptive psychology” (2001:3). Relating to intentionality and to a descriptive analysis of intentional lived experiences, Scanlon insists that phenomenology may be regarded as a descriptive psychology. As this brief consideration of the directions of phenomenology demonstrates, it is the diversity of directions that have been developed that makes the theory of phenomenology sometimes difficult to grasp. If bearing in mind how PCP has developed and still is developing, not least in educational research settings, it may not be too difficult to realize that other theories do the same. What does personal

construct psychology envision the individual doing? First, like a

scientist,

forming constructs with which to make sense of the world. Then, the

individual

tests those construct. In a solipsistic world there would be no need to

test

one’s construct: indeed we may wonder at the process of forming them in

the

first place! But in all other worlds with which we are familiar, the

individual

attempts to compare his or her meaning with that of another, or others,

of his

or her species. That activity in personal construct psychology is an

activity

of validating one’s constructs…what is built firmly into the theory is

the

notion that

one goes to one’s social

context to

validate one’s construing. (

Pope & Denicolo (2001) discuss the social aspects in education from the point of view of Kelly’s Sociality Corollary. Referring to classroom interaction, they note that: “change in construing will only take place if the person experiments with his/her ways of seeing things, construes the implications of these experiments and sees that it would result in an elaboration of his/her construct system, if he/she were to adopt an alternative way of seeing things”. Further, they argue that “talking about ideas and listening to conflicting opinions of others and the putting of these ideas to the test would represent an approach to teaching which is consistent with Kelly’s model of ‘man-the-scientist’”. Indeed, it is difficult to understand how ‘the social’ could not be part of PCP in educational research. It is rather a matter of ‘ground’ and ‘figure’ – in some settings it is foregrounded more than in others. Another crucial issue which has had a huge impact on educational research, and particularly in research designs, is the alternative metaphor: ‘person-the-storyteller’ (Pope, 1995; Pope & Denicolo, 2001). This has led to a variety and diversity of different methods, alternative techniques to repertory grids, and, in this way, has been fruitful in opening up other interpretative approaches. The richness and novelty in many of the research projects within the realm of the alternative metaphor is certainly a way of reaching “expandability by integration with other approaches” (Winter, 2007:6). It also shows that, just like phenomenological research, constructivist research reaches out to and draws from adjacent theories and orientations. There is however, for this very reason, a need to be observant to what authors really mean when they refer to, for example, ‘constructivist research’ and ‘PCP research’ or ‘phenomenological research’ and ‘phenomenology’ in their writings. A phenomenological perspective and phenomenological study In this section, the focus will primarily be on phenomenology and the differences between what Patton calls a ‘general phenomenological perspective’ and ‘phenomenological study’. In some commonly used books on research methods (i.e. Patton, 1980/1990; Taylor & Bogdan, 1984), the sphere of research is divided into two major theoretical perspectives: ‘positivism’ and the ‘phenomenological perspective’. Phenomenology is described as a broad tradition within social science which is concerned with understanding from participants’ frames of reference. This very broad description could, more or less, include any qualitative, interpretative research, and it certainly appears to diminish the significance of the immense phenomenological contribution to theory and thinking in philosophy. In this way phenomenology becomes a very simple, clear and straightforward way of doing research. The main aims appear, as presented, to be bipolar to the positivist paradigm. Thus, the concept of phenomenology is complex due to the fact that it is sometimes referred to as a ‘philosophy’, sometimes as a ‘perspective’, ‘approach’, inquiry’ and, on some occasions, as a ‘paradigm’. Immediately after these considerations, Patton introduces phenomenology as both an ‘approach’, as well as an ‘inquiry’. For the reader not familiar with phenomenology, it must appear not only as complex, but also confusing. There is dissimilarity between the philosophical phenomenology and the practical approach to social science often referred to as phenomenology in several research handbooks. In Merleau-Ponty can be said to represent an existential phenomenology. His writings are less dogmatic than Husserl’s and closer to constructivist thinking as is illustrated when he writes that “we must not, therefore, wonder whether we really perceive a world, we must instead say: the world is what we perceive “(Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p.xi). This could be compared to the PCP view that an individual creates his/her own way of seeing the world. Mereau-Ponty’s definition of ‘essence’ is likewise close to constructivist thinking: Looking for the world’s essence is not looking for

what it is as an idea once it has been reduced to a theme of discourse;

it is

looking for what it is as a fact for us, before any thematization. (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. XV)

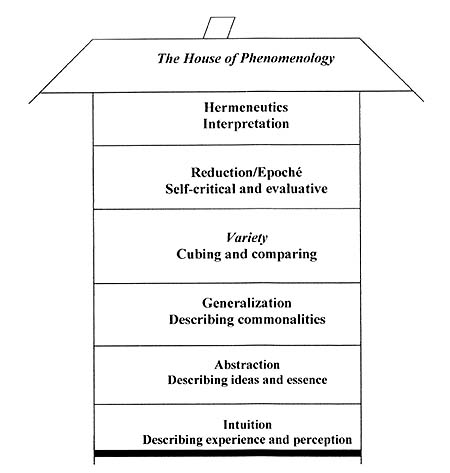

It is not simply the position that Merleau-Ponty takes on the concept of ‘essence’ that he has influenced so many, but also his extensive writings on intentionality, temporality and experience. His elaborated notion of ‘intentionality’ could be one bridge between phenomenology and PCP, which Butt has already suggested (1997 and 2004). For those not familiar with the term ‘intentionality’, it was introduced by the German psychologist Bretano in the 1870s, but it has been developed, extended and redefined by, amongst others Husserl (a student of Brentano) and Merleau-Ponty. In short one can say that intentionality is the very act of ‘directing our consciousness towards something’ and it is how we reach out to events in the world and make sense of them. It is through intentionality, as van Manen argues, that we can ‘discover a person’s world or landscape’ (1990, p.182). Understood in this way, intentionality resembles the constructivist ‘process of construction’. When elaborating on the notion of intentionality van Manen introduces the terms ‘specific intentionality’ and ‘general intentionality’. Specific intentionality refers to directness of thinking here and now and to our direct experiences of certain phenomena. General intentionality, on the other hand, has to do with a general directness to the world and how we choose and find ourselves to be presented in the world – how, for example, we think and act as teachers. In my research on language teachers’ experiences of teaching and change, general pedagogic intentionality (thematic categories) was extracted from a series of extensive interviews, as one of the final steps in the analyses (Apelgren, 2001). Both these perspectives of intentionality have relevance for a theory of personality, such as PCP. Merleau-Ponty has also written about ‘temporality’, which could be described as ‘lived’ or subjective time as opposed to objective or clock time. A former experience, something past, and a forthcoming experience, something in the future, have to be brought into our consciousness in the here and now (Merleau-Ponty, 1962). This suggests that lived experience has a temporal structure, thus implying that it can never be grasped directly but only reflectively and, as such, changes by the influence of the present time. Put another way, van Manen describes this as the way in which “the temporal dimensions of past, present, and the future constitute the horizons of a person’s temporal landscape” (1990, p.104). Zaner has in his book The Way of Phenomenology discusses the complex structure of temporality and concludes that temporality is “easily grasped, but devilishly difficult to express in words” (1970, p.142). The theory of how, as individuals, we experience different dimensions of time has bearing on PCP research studies in education. One example where analysis of recollections close to the phenomenological ‘temporality’ can be found in Burnard’s study on children’s experiences of improvising and composing music (1999). So far, my aim has been to attempt to advance the idea that one way in which phenomenology can actually contribute to constructivist educational research is in its philosophy. The notions, for example, of intentionality and temporality, as shown above, can provide a theoretical framework to compare and discuss empirical results in an additional, theoretical, manner. Phenomenological analysis may also be looked at in relation to constructivist analyses within personal construct theory, for example by means of repertory grids and different narrative techniques. PHENOMENOLOGICAL AND CONSTRUCTIVIST ANALYSES The procedures commonly used to elicit experience of different phenomena in phenomenological analysis (Patton, 1990; van Manen, 1990; Bjurwill, 1995; Smith & Osborn, 2008), could well be used in constructivist analysis as yet another complement to the variety of methods within PCP educational research (Pope & Denicolo, 2001). A phenomenological analysis is often described as a disciplined analysis and is often concerned with detailed stage by stage analyses of transcribed interviews. There are today numerous different phenomenological analyses used, i.e. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis, or IPA for short, (Smith, 1997; Smith & Osborn, 2008) or Phenomenological psychological analysis (Giorgio & Giorgio, 2008). The technique referred to and used here is close to what has been named ‘empirical phenomenological psychological analysis’ (EPP, Karlsson, 1994) and to introduce this phenomenological analysis, the metaphor of the House of Phenomenology will be used (Bjurwill, 1995; described and developed in Apelgren, 2001 and 2003).  Passing between the different floors of the house, the reader probably realizes that the researcher takes a different perspective in his/her analysis of the phenomenon on every floor. This way of “attacking” one’s subject, is relevant for all types of analysis of interpretative research and is, of course, something constructivist researchers do all the time in their interpretative work. In a phenomenological analysis it is rather a matter of being more actively observant of different perspectives. Lemon & Taylor (1997) describes five stages of a phenomenological analysis which has features in common with the different floors in the house of phenomenology; (1) make sense of the text/read and reread, (2) extract significant statements, (3) reflecting on the statements, (4) themes of related meaning and (5) description of phenomenon. In my own research (Apelgren, 2001 and forthcoming) I have explored teachers’ thinking and experiences of different educational concepts, combining analyses from PCP (repertory grid and career rivers/snakes) with different analytical tools used in phenomenological research (empirical phenomenological psychological analysis and text analysis using NVivo 8). These multi-dimensional analyses have been used in addition to more individual or narrative presentations. To see how the EPP analysis works in practice, examples from research on foreign language teachers personal theories and experiences of teaching and change in teaching will be given (Apelgren, 2001), referring back to the House of phenomenology above. In short the study was set up as a cumulative study, starting with a questionnaire survey to 70 foreign language teachers in one urban educational area. Twenty teachers from the cohort were interviewed twice and were also asked to comment on the final analyses and results. The first interview was an instructed narrative conversation based on their own drawings of career rivers/snakes, where the participants told “their” teaching career stories focused around experiences of teaching, subject matter issues and change and development. In the first stage of the analysis (floor 1; intuition, describing experience and perception) potentional interpretations of meanings appear which lead to the second stage of the analysis (floor 2; abstraction, describing ideas and essence). All in all 334 statements/quotations were isolated as examples of specific themes to be further explored in the second interview. In addition, those quotations made the base for the narrative descriptions in the study. Data from the two interview transcripts were read and reread as to be able to describe commonalities (floor 3) within the 40 interviews related to common themes explored. In the forth stage the statements were grouped into separate themes of experiences of teaching and experiences of change, so called ‘specific intentionality’ (van Manen, 1990), which refers to directness of thinking here and now and to our direct experiences of certain phenomena, in this case teachers’ thinking and experiences of teaching foreign languages and developing as a foreign language teacher. In the fifth and final stage the extracts were reduced into thematic categories, so called ‘general pedagogic intentionality’ (floor 5). At this point the researcher has moved away from the actual transcript interview data and it thereby becomes the researcher’s text more than the informants’ texts. Here the extensive interview data were reduced to four different orientations towards foreign language teaching. The table below shows qualitative different ways of experiencing language teaching based on the participants’ self-perception of teacher role and personal theories of English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching. The four categories presented in the table indicate that teaching EFL is viewed as being oriented towards one of the following categories: (1) teaching as a mutual affair, (2) teaching as guiding with an invisible hand, (3) teaching as a social activity, and finally (4) teaching as being a captain on a ship.

Different ways of experiencing teaching of EFL

(Figure 26.

Apelgren, 2001:295)

In the above I have put forward the idea of general pedagogic intentionality as a way of describing foreign language teachers’ orientation of their teaching and ways of changing. The way an individual teacher changes depends to great extent on personal factors which in a subtle way will guide how changes come about. The choice of listening and learning from external agencies, curriculum demands, collegial interaction or experienced teachers’ expertise, is a personal and selective choice which is governed by past experiences. Seen in this way “we carry around our past with us in our construing” (Burr & Butt, 1992, p.63). The way a teacher experiences and views his or her teaching is also personal. I have indicated that the teachers’ understanding of their teaching can be described as being directed in different ways, with different goals and perspectives. The foreign language teachers in this study define English as a foreign language and their descriptions emphasize either language as a system or language as communication. However, it is seldom a matter of ‘either or’, as language must be understood as to enclose both aspects, insofar that language is a system which enables, permits and is used for human communication and interaction. This implies that the interpretation and the choice of focus in that interpretation lie with the individual teacher and his or her ways of making sense. In a traditional phenomenological analysis the researcher continues to fine-tune the interpretation in order to reach the essence of the phenomenon. In my study, I wanted to place the phenomenological results within the constructivist framework. The categories of general pedagogical intentionality were therefore taken back to the participants for comments on which of the four orientations they found best correspond to how they saw themselves as foreign language teachers. I have here tried to show that there is a potential in using a combination of logical analysis with a qualitative analysis of empirical and personal data. Also Sages & Szybek (2000) have, in a study of comprehensive school students’ knowledge of biology, shown how phenomenological analysis can be used on students’ texts. Their aim has been to elucidate how scientific concepts presented to pupils in school are understood and how a phenomenological analysis could complement a research area where constructivism is a common theoretical base. CONCLUSION In this paper, the aim has been to present both theoretical reasons for, as well as empirical examples of, the use of phenomenology in PCP educational research. The title “overlapping intellectual communities at work” suggests that different approaches and theoretical perspectives can exist – and sometimes coexist – and thereby mutually benefit one another. For this to be possible, certain prerequisites, such as ontological issues, need to be clarified. It has been suggested that Husserl and his followers of traditional philosophical phenomenology stand too far from the fundamental assumptions of personal construct psychology. In the philosophy of the existential and hermeneutic phenomenology on the other hand, there seems to be much to gain from their theories and ideas. The concepts of ‘intentionality’, ‘temporality’ and ‘lived experience’ have briefly been touched and commented upon. In addition, practical aspects, such as phenomenological analysis, have been discussed and presented as a possible tool to better understand empirical data. Pope and Denicolo (2001:xi) point out that “Personal Construct Theory provides a fruitful framework within which to explore education”. Referring to the above discussion, I would argue that phenomenology, and more precisely phenomenological techniques and tools of analyses, are equally fruitful in exploring education. Within phenomenology, there are people who propose that phenomenology should be accessible to a wider audience. Halling (2002), for one, discusses different ways in which phenomenology could be fruitful and useful. One important reason for adopting a phenomenological approach is to provide a deeper understanding of specific experiences to practitioners who work with persons having those experiences, in our case teachers and educators. Moreover, such techniques would also provide important empirical evidence for policy makers. It is easy to recognize the proximity to recent PCP research in education when Halling, referring to Bruner (1986) and the importance of telling the participants’ stories, argues that “… if the researcher tells the story of the research, the reader is invited to think along and to participate in the experience of discovery that was part of the research process” (2000:27). Moses concurs with this view when stating that “…philosophy as educational research provides educators and researchers alike with fundamental understanding of the fundamental aims and meanings of education. Such theoretical work both adds to and informs issues within the larger study of education, such as teaching, learning, and policy” (2002:6). Thus, it would appear that van Manen and the hermeneutic phenomenology can be seen as a theoretical perspective in between, on the one hand, the more philosophical phenomenology of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty and, on the other, the practicality of for example Bogdan & Tayor (1984). Whilst this approach is still close to the traditional philosophy of phenomenology and follows in many ways its classic research methods and procedures (like thematic analysis, reduction and description), it is also close to, and grounded in, people’s experiences (through interviews, observations, journal writings etc.) and empirical work that constructivists in educational research recognize and are familiar with. That encapsulated in the words of Phillips below may well be written about personal construct psychology: The

essence of

hermeneutical approach is that humans harbor beliefs, intentions,

desires, and

so on, and these things lead to human action and are therefore

necessary

ingredients in any attempt to understand and explain action

(Phillips,

1997:1016)

For van Manen, hermeneutic phenomenology is “a philosophy of the personal, the individual” (1990, p.7). What then could be more appropriate to accompany a theory of personality than a philosophy of the personal, especially if the task of the philosophical research is, as van Manen points out, “to construct a possible interpretation of the nature of a certain human experience” (van Manen, 1990, p.41). Indeed, this is very close to what we as constructivist educators are also trying to accomplish in our research. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| REFERENCES | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Apelgren,

B.M. (2001). Foreign language

teachers’ voices. Personal theories and experiences of change in

teaching English as a foreign language in Apelgren, B.M. (2003). Researching lived experiences: A study on Swedish foreign language teachers’ voices on teaching and change.In G. Chiari & M. L. Nuzzo (eds.) Psychological constructivism and the social world. Milano: FrancoAngeli. (pp. 132-141) Apelgren, B.M. (2005). Research on or with teachers? Methodological issues in research within the field of foreign language didactics. In E. Larsson Ringqvist & I. Valfridsson, Forskning om undervisning i främmande språk. Växjö: Apelgren, B.M. (work in progress) Bengtsson, J. (Ed.) (1999) Med livsvärlden som grund. Bidrag till utvecklandet av en livsvärldsfenomenologisk ansats i pedagogisk forskning. Lund: Studentlitteratur. Bengtsson, J. et al (2000). Pedagogisk forskning med livsvärlden som grund. Nordisk pedagogik, 20, 124-127. Bjurvill, C. (1995). Fenomenologi. Lund: Studentlitteratur. Burnard, P. (1999). Into different worlds: children’s experiences of musical improvisation and composition. Unpublished PhD, University of Reading, UK. Butt, T. (1997). The later Kelly and existential phenomenology. In P. Denicolo,P. & M. Pope (eds.), Sharing understanding and practice. Farnborough: EPCA Publications. (pp. 40-49) Butt, T. (2003). The phenomenological context of personal construct psychology. In F. Fransella, (ed.). International Handbook of Personal Construct Psychology. Butt, T. (2004). Understanding, explanation, and personal construct. Personal Construct Theory & Practice, 1, 21-27 Butt, T. (2007) Personal construct theory and method: Another look at laddering. Personal Construct Theory & Practice, 4, 11-14. Butt, T. & Burr, V. (1992). Invitation to personal construct psychology. London: Whurr Publishers Ltd. Claesson, S. (2008). Livsvärldsfenomenologi och empiriska studier. (Life world phenomenology and empirical studies). Nordisk pedagogik, 28, 123-131. Dahlin, B. (2000). (Review). Med livsvärlden som grund. Bidrag till utvecklandet av en livsvärldsfenomenologisk ansats I pedagogisk forskning. Nordisk pedagogik, 20, 55-57. Fransella, F. (2007). PCP: A personal story. Personal Construct Theory & Practice, 4, 39-45 Giorgio, A. & Giorgio, B. (2008). Phenomenology. In: J. A. Smith (ed.) Qualitative psychology. A practical guide to research methods. (Second edition).London: Sage. (pp. 24-52) Halling, S. (2002). Making phenomenology accessible to a wider audience. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 33, 1-38. Hilgard, E.R. (1997). History of educational psychology. In: D. Berliner & R. Clafee (eds.), Handbook of educational psychology. Husserl, E. (1913/1931). Ideas. Kelly, G. A. (1955/1963). A theory of personality. New York: Norton. Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception. (French original 1945) . Moses, M. (2002). The heart of the matter: Philosophy and educational research. Review of Research in Education, 26, 1-21. Patton, M.Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods.Newbury Park, California: Sage. Pope, M. (1995). Constructivist educational research: A Personal Construct Psychology perspective. Keynote paper presented at the 11th International Congress of Personal Construct Psychology, Barcelona, 3-7 July 1995. Pope, M. & Denicolo, P. (2001). Transformative education. Personal construct approaches to practice and research. London: Whurr. Pope, M. & Keen, T. R. (1981). Personal construct psychology and education. Raskin, J. (2002). Constructivism in psychology: Personal construct psychology, radical constructivism, and social constructivism. American Communication Journal, , 5, 2002, 1-25. Raskin, J. (2006). Don’t Cry for Me George A.Kelly: Human involvement and the construing of personal construct psychology. Personal Construct Theory & Practice, 3, 50-61 Sages, R. & Szybek, P. (2000). A phenomenological study of students’ knowledge of biology in a swedish comprehensive school. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 31, 155-187. Scanlon, J. (2001). Is it or Isn’t it? Phenomenology as descriptive psychology in the logical investigations. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology,32, 1-11. Smith, J.A. (1997). Developing theory from case studies: Self-reconstruction and the transition to motherhood. In N.Hayes (ed.) Doing Qualitative Analysis in Psychology. Erlbaum Smith, J.A. & Osborn, M. (2008). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (ed.) Qualitative psychology. A practical guide to research methods. (Second edition).London: Sage publications. (pp. 53-80) Taylor, S. & Bogdan, R. (1984). Introduction to qualitative research methods. van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience. von Glasersfeld, E. (1991). Radical constructivism. Warren, B. (2004). Construing constructivism: Some reflections on the tension between PCP and social constructivism. Personal Construct Theory & Practice, 1, 34-44 Winter, D. (2007). Personal construct psychology: The first half-century. Personal Construct Theory & Practice, 4, 63-67. Zaner, R. (1970). The way of phenomenology. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ABOUT

THE

AUTHOR Britt

Marie Apelgren, PhD, is

Senior Lecturer and Vice Dean at the Faculty of Education of the University of Gothenburg. Her primary research field concerns teachers’

and

students’ perceptions and experiences of language teaching. Her

theoretical

framework is constructivist, primarily influenced by personal construct

psychology. Other research areas involve students’ language skills in

English

and charting and delineating teachers’ alternative forms of assessment. Britt

Marie Apelgren, PhD, is

Senior Lecturer and Vice Dean at the Faculty of Education of the University of Gothenburg. Her primary research field concerns teachers’

and

students’ perceptions and experiences of language teaching. Her

theoretical

framework is constructivist, primarily influenced by personal construct

psychology. Other research areas involve students’ language skills in

English

and charting and delineating teachers’ alternative forms of assessment.Email: BrittMarie.Apelgren@ped.gu.se |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| REFERENCE Apelgren, B. M. (2010). Overlapping intellectual communities at work: (Retrieved from http://www.pcp-net.org/journal/pctp10/apelgren10.html) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Received: 31

August 2009 – Accepted: 28 January 2010 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

ISSN 1613-5091

| Last update 11 February 2010 |